THE INDUSTRY OF WAR: FOXHOLE’S PLAYER DRIVEN WAR ECONOMY

Source - Foxholegame.com

Procedural rhetoric begins with a simple premise: games persuade through mechanics. They shape interpretation not only through story or dialogue, but through systems, constraints, and feedback loops. The question is therefore not whether a game’s mechanics and systems contain meaning, but what that meaning is and how it is constructed.

In Foxhole, the most distinctive system is its player driven war economy. Every weapon is manufactured. Every vehicle is assembled. Every crate of ammunition is transported by another human being. Combat depends on labor. Loss depends on supply. The question this article explores is straightforward: what is Foxhole attempting to persuade the player of through this industrial design?

How the War Is Built

Foxhole’s logistical chain operates in stages. Raw materials are extracted from resource nodes scattered across the map. These materials must be transported to refineries, processed into usable components, then delivered to factories where weapons, vehicles, and construction supplies are manufactured. From there, finished goods are loaded into trucks, trains, ships, or now aircraft, and moved toward active frontlines.

The system is persistent. Wars last weeks. Factories operate continuously. Supply depots deplete in real time. There is no automated spawning of advanced equipment. If the chain breaks at any point, frontlines collapse. Ammunition shortages stall offensives and fuel scarcity immobilizes armored divisions.

Combat is therefore downstream. Infantry engagements, artillery duels, tank pushes, even naval operations all depend on infrastructure that most players will never directly see. Destruction is immediate. Production is slow. The asymmetry is a deliberate and ingenious design.

None of this is cosmetic simulation. It is structurally binding. The frontline and the factory are mechanically inseparable.

The Persuasion: What the System Teaches

What does this structure persuade the player of?

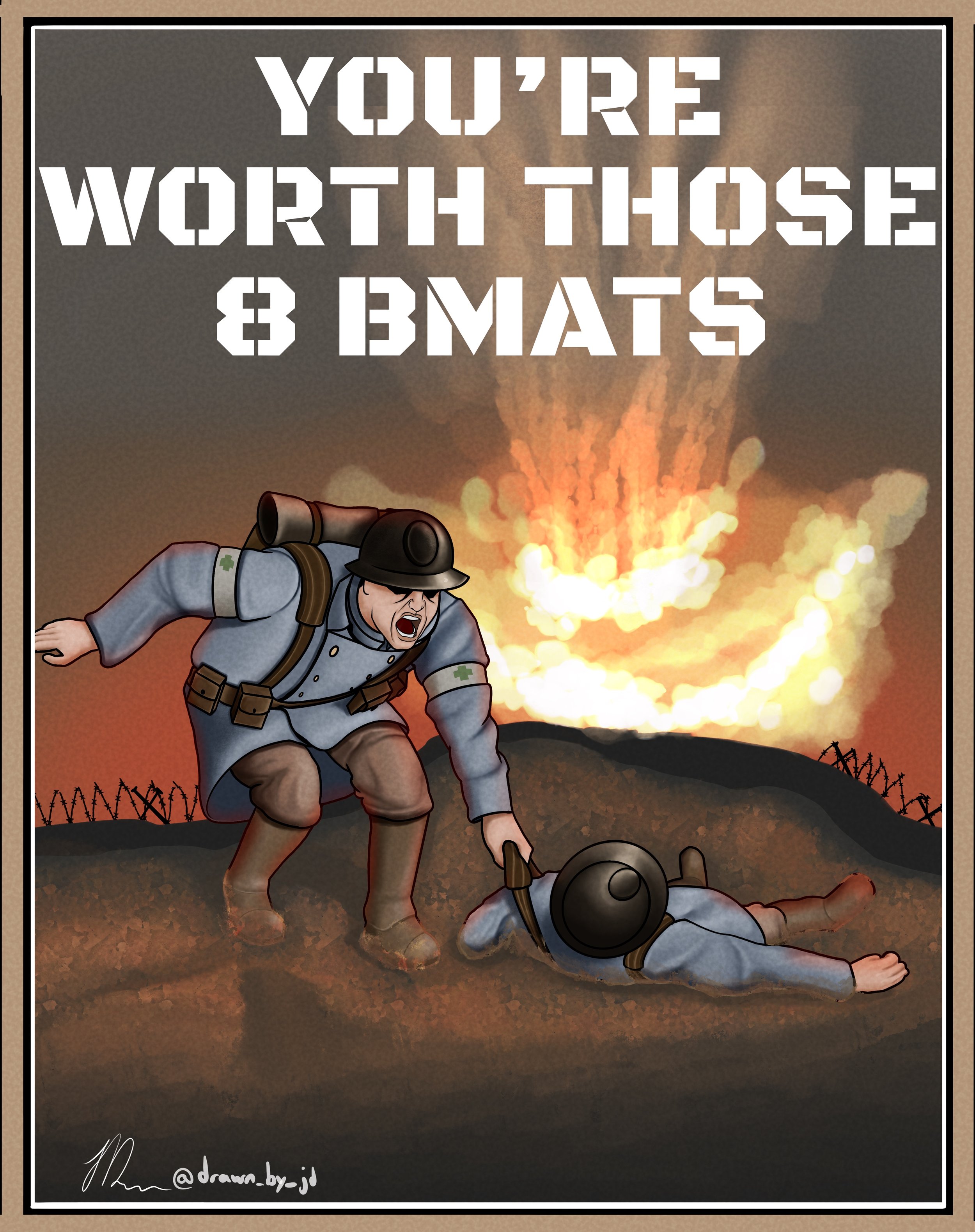

First, it reframes war as industry before heroics. The traditional power fantasy of the lone soldier gives way to dependency. Every bullet carries embedded labor. A destroyed tank represents not only tactical loss, but the loss of accumulated effort. On the frontline, players often joke that “your life is only worth eight Bmats.” Basic Materials, the foundation of most equipment, become a unit of human value. The humor lands because it reflects a mechanical truth. Through repetition, the player internalizes cost. Waste feels different when you mined the sulfur and components yourself. A reckless charge is no longer cinematic bravado. It is inefficient expenditure.

Image courtesy of Discord user jd_0046 on the official Foxhole Discord server

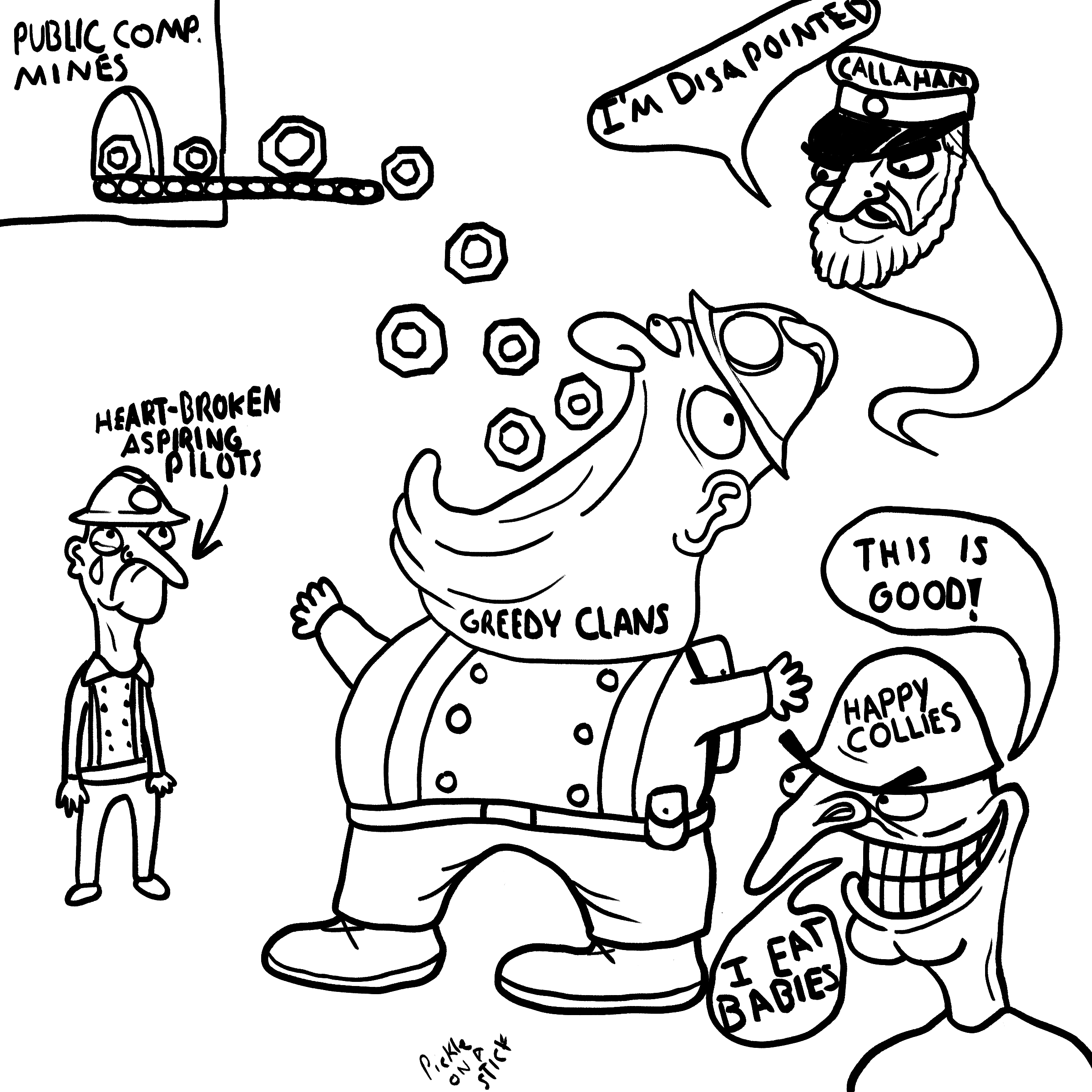

Second, the system normalizes interdependence. Some players specialize entirely in logistics. Others organize transport convoys. Regiment leaders coordinate industrial output rather than battlefield tactics. Combat effectiveness becomes collective performance rather than individual skill. Resource scarcity makes this interdependence visible. Large regiments capable of mining and stockpiling at scale gain influence over what gets produced and where it is deployed. The community response, captured in the phrase “clan man bad,” reflects tension born directly from mechanical imbalance. Production capacity is finite. Factory queues are contested. Decisions about whether to prioritize tanks, artillery shells, bunker supplies, or aircraft generate real disagreement. Herein, the game does not verbally argue for cooperation but makes it structurally necessary. It also makes hierarchy inevitable.

Image courtesy of Discord user pickleonastick on the official Foxhole Discord server

Third, Foxhole subtly shifts the player’s identity. You are not merely fighting in a war or pushing a frontline until an important objective is reached. You are sustaining one. The economy becomes a moral weight of sorts. Abandoning a supply run has consequences. Overextending heavy armor without logistical support risks hours, or even days of effort. Coordination expands beyond the battlefield into spreadsheets, Discord servers, and faction wide initiatives such as Warden Alliance or Colonial Sigil. Production quotas are discussed. Strategic priorities are negotiated. The player begins to think in terms of sustainability, throughput, and efficiency rather than personal glory.

This is procedural rhetoric in its clearest form. The game does not explain that modern warfare is a product of industrial systems, hierarchy, and material constraint. It compels the player to experience that reality directly.

Why This Matters

Foxhole’s persuasion operates quietly. It does not rely on spectacle or scripted drama. Its most ambitious statement is embedded in its supply chain. By making production visible and consumption costly, it constructs a philosophy of interdependence that few multiplayer games attempt.

Understanding this procedural rhetoric has practical implications. It explains why Foxhole retains players for months. It clarifies why marketing the game as a “war MMO” only captures part of its appeal. The true hook lies in participation within a functioning system. Players are not sold momentary action. They are sold relevance.

Other war games simulate combat. Foxhole simulates infrastructure. Titles such as EVE Online similarly foreground player driven economies, yet Foxhole grounds that economic logic directly in territorial warfare. Even large scale shooters such as Battlefield 1 abstract logistics into background mechanics. Foxhole makes them unavoidable.

On the surface, it appears modest. Underneath, it advances one of the most persuasive systemic arguments currently available in multiplayer design: that war is sustained not by spectacle, but by labor.

And once that lesson is learned, it becomes difficult to unsee it, both in games and beyond them.