THE PROCEDURAL ONTOLOGY PYRAMID: READING POLITICS IN GAMES

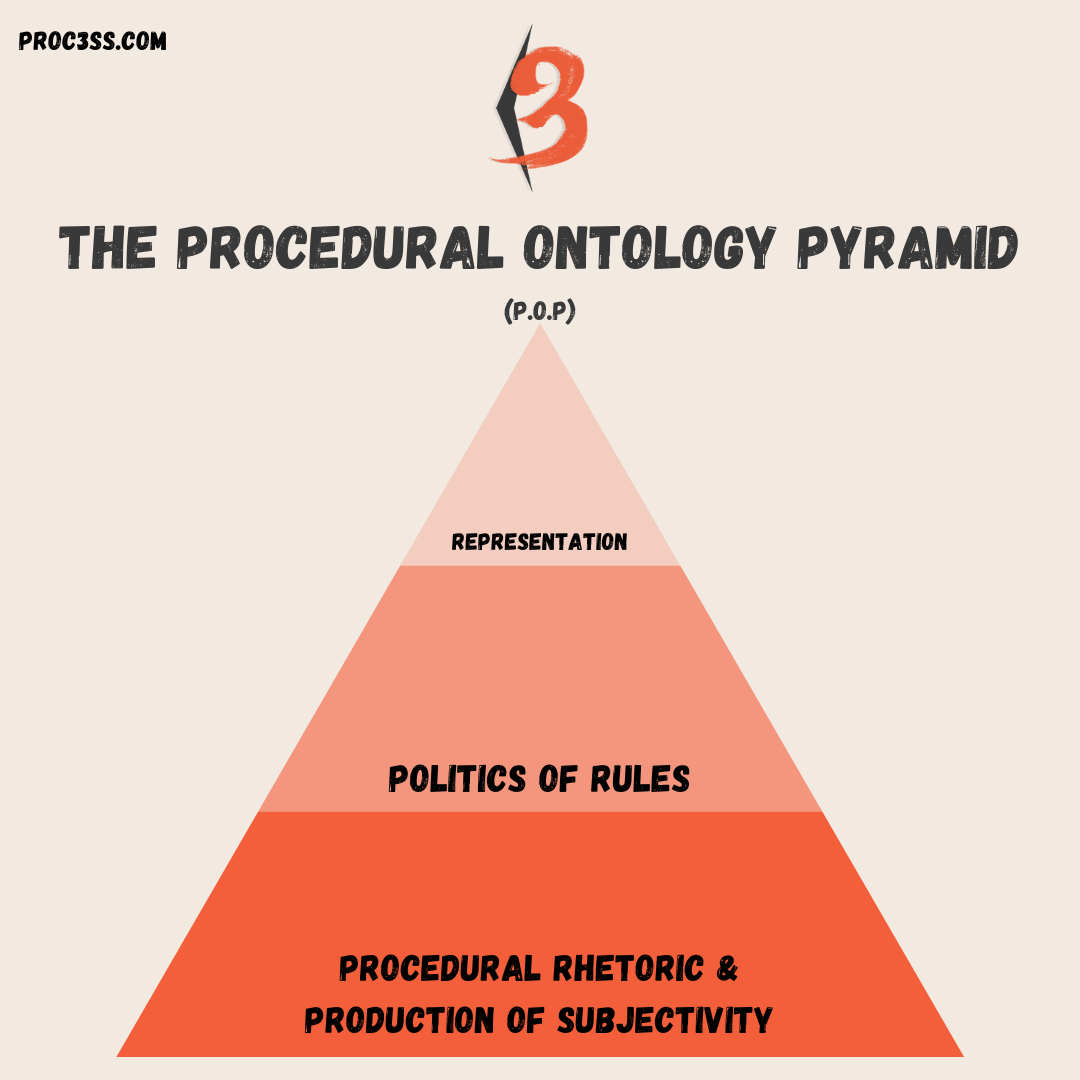

The Procedural Ontology Pyramid (P.O.P) - Younes Barakat (2025)

When we play, it feels like freedom. We choose where to go, what to do, how to act. But behind every moment of agency in a video game lies a hidden architecture of systems guiding, nudging, and sometimes deceiving us. French philosopher Mathieu Triclot proposed that video games can be understood across three strata, or layers of discourse that shape the player’s experience. They reveal how games are never neutral, but always charged with ideology, culture, and persuasion.

Yet while Triclot’s three-strata model offers a powerful descriptive framework, its deepest layer remains focused on modes of play. Particularly multiplayer structures and rule configurations. In doing so, it ultimately treats the lowest stratum as a variation of formal organization rather than as a site of ontological transformation. This article proposes what I call the Procedural Ontology Pyramid (POP), a reformulation of the three-strata model that reorders its analytical priorities and deepens its theoretical scope.

In POP, the third layer is not concerned with additional rule structures or social configurations of play. It analyzes something more fundamental: how procedural systems shape subjectivity itself. Drawing on Ian Bogost’s procedural rhetoric, this layer examines how interaction, feedback loops, constraints, and consequences do not merely organize gameplay, but actively condition the player’s sense of agency, responsibility, and freedom.

The top layer: Representation

The most visible layer is representation: the world of images, dialogue, and story. A dystopian city, a noble hero, a corrupt regime. This is the surface-level discourse of games, where politics and philosophy are carried by theme and setting.

In Elden Ring, for example, representation comes in the form of the Lands Between. A fractured realm of fallen gods, shattered order, and endless decay. Its castles, swamps, and catacombs are not just fantasy backdrops but symbolic echoes of corruption, hubris, and cyclical ruin. Even before you swing a sword, the game is making a statement about decline and the burden of inheritance.

The structural layer : Politics of Rules

Beneath representation lies the structural layer. At this level the game argues through rules and models. If the surface persuades through the explicit, in other words the story, aesthetics or music, then this layer persuades through constraint. Here, the game does not tell you what the world means. It defines what the world is and allows. Stealth systems, enemy detection patterns, resource economies, progression trees, simulation logics, these are not neutral mechanics. They model how a world functions. They establish causal relationships. They define what counts as success, failure, efficiency, or excess.

In SimCity, urban life is modeled as a system of optimization and growth. Budget balance, zoning logic, and infrastructural efficiency quietly structure a technocratic worldview. The persuasion does not occur through narrative, but rather through the constraints of the simulation itself. This is the second mode of persuasion: arguing through rules, through models, through the architecture of possibility.

If representation shows what a world looks like, the structural layer is what defines its operation. However, it still stops short of the deepest, foundational level, because while it structures action, it does not yet explain how the player is shaped by repeatedly inhabiting those constraints and rules.

The foundational layer: Production of Subjectivity

The deepest stratum is the most powerful and the least visible. Here, games no longer tell stories or enforce rules; they shape the players themselves through procedural rhetoric. Through feedback loops of success and failure, reward and punishment, games produce subjectivity: the way we see ourselves within the system of the game.

Consider Dark Souls, which slowly transforms frustration into determination, training players to embrace death not as failure but as progress. Every defeat is a lesson: enemy patterns become more familiar, paths less intimidating, and the world gradually more knowable. What begins as despair shifts into mastery, but only through perseverance.

This loop reshapes the player’s relationship to suffering itself. Death ceases to be an end and becomes a resource, a necessary condition of growth. The game persuades you, at the deepest level, that struggle is meaningful, that repetition is not futility but the only path to transcendence. Camus would certainly have been a great fan of souls-likes.

In Dishonored, the production of subjectivity is found in how the game makes you feel about your freedom. Every assassination, every act of mercy reshapes not only the world but also your sense of responsibility within it. The game enacts Sartre’s existentialism: you are free, but condemned to bear the weight of your choices.

Why the Procedural Ontology Pyramid Matters

Together, the three layers remind us that games are not empty entertainment. They are layered systems of persuasion:

Representation shapes our imagination.

Rules structure our action.

Production of subjectivity transforms how we think and feel.

This is why games are such powerful cultural artifacts. They do more than depict ideas, they embody them, train us in them, and make us live them.

To read games critically, then, is to peel back these layers. What do the images show? What do the rules enforce? And how do they shape who we become as players?

Toward Critical Play

Understanding the procedural ontology pyramid gives us a toolkit for navigating the politics of games. It allows us to see that freedom in games is always constructed, that rules always carry values, and that subjectivity is always being shaped by play.

In the end, games are far from simple mirrors of culture, they are engines of it. And by reading across these three layers, we can better understand not only the games we play, but the world they model and the selves they produce.