WHEN GAMES ARGUE: PHILOSOPHY AND THE RHETORIC OF GAMES

Most people think of video games as stories with buttons. A hero, a quest, some dialogue, and maybe a branching ending. But games do more than just tell stories. They argue. For most gamers it's pretty evident that games communicate to us through cutscenes or scripts, but it is less evident when they do so through the very systems and rules that govern play.

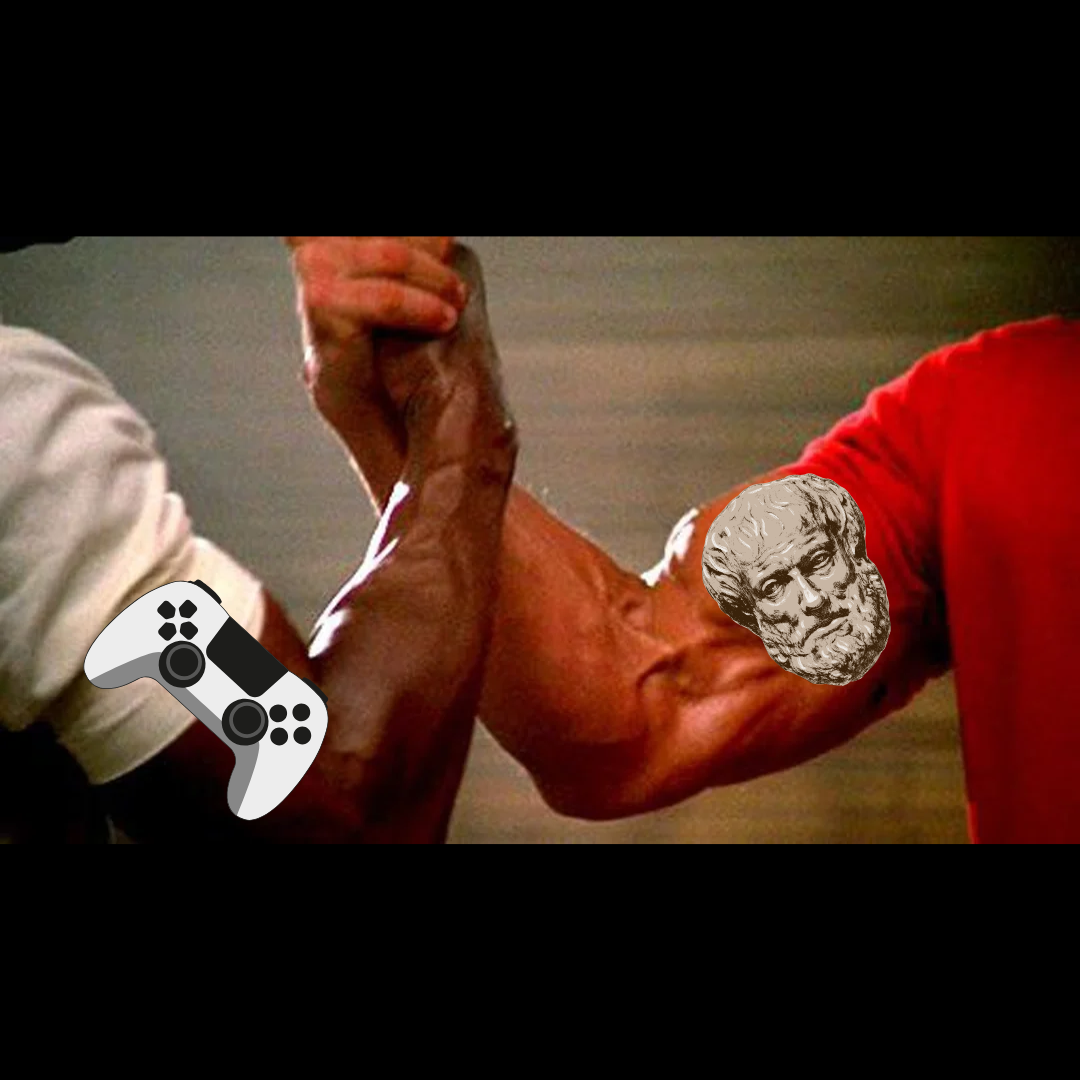

This is what media theorist Ian Bogost calls procedural rhetoric: the idea that games communicate by procedures, by the ways they structure choices, actions, and consequences. And it’s what makes games unique and superior compared to media such as movies and music. They do more than just show us a world, they ask us to inhabit its logic.

Procedural Rhetoric: Rules as Argument

Think about chess. It doesn’t have characters or dialogue, but it teaches you something through its design: that victory comes from foresight, sacrifice, and strategy. The rules themselves are the rhetoric.

Video games do the same, only on a much larger and more complex scale. A survival game like Don’t Starve persuades players that life is precarious and resource management is everything. Papers, Please models the suffocating logic of bureaucracy, making you complicit in its cruelty.

Unlike films or novels, where the message is delivered in fixed form, games force players to participate in meaning-making. Every choice, every input, every mechanic is part of the argument.

Derrida and the Play of Systems

This is where philosophy comes in. Jacques Derrida, the French philosopher of deconstruction, argued that meaning is never fixed, it is always deferred, shaped by difference, what he called différance. Structures don’t have a stable center; they shift, opening up interpretation.

Games embody this perfectly. Their systems don’t dictate a single meaning but create fields of play where meaning emerges from interaction. Take an immersive sim like Dishonored: whether you play lethally or non-lethally, stealthy or loud, the game doesn’t tell you what it means to do so. No. You construct that meaning through your actions.

Derrida also spoke of the trace, a rather complex concept in which presence always carries an absence or is marked by it. In games, this lives in what’s hidden, the paths not taken, the quests you ignored, the consequences unseen. These absences still shape the experience. What you don’t do in a game often matters as much as what you do, as i'm sure many of you have experienced browsing youtube trying to achieve a different ending to a game you enjoyed.

Games as Philosophical Texts

If we follow Bogost and Derrida together, games aren’t just entertainment but philosophical texts, not written in words, but in systems and procedural logic. Where novels use metaphor and films use montage, games use mechanics and feedback loops.

This is why studying games on a procedural level matters for philosophy, culture and marketing alike. They are the first medium in history where meaning is not only consumed but enacted. We don’t just interpret games; we live their arguments through play. How powerful is that ?

Toward a Philosophy of Play

Thinking about games this way changes how we see both philosophy and gaming. It means a game like Dark Souls isn’t just “hard”; it’s a meditation on persistence, failure, perseverance and repetition. It means Civilization isn’t just a strategy sim; it’s a discourse on progress, empire, and control.

And it means that when we play, we aren’t just passing time, on the contrary, we’re participating in living systems of thought. Games are very rarely neutral; they shape how we see freedom, morality, community, and even ourselves.

As Derrida might say, the center is always deferred. And in games, that deferral is where play and philosophy truly begins.